Phoebe Snetsinger: Cancer and Birding

“At the time, there was no proven effective treatment for melanoma; neither radiation nor chemotherapy had been shown to have any significant beneficial effect. Therefore, I wasn’t under pressure to take any standard follow-up treatment simply because there wasn’t any. There were some experimental possibilities, but at least one of these was a lengthy, totally deliberating, even life-threatening process-which was easy for me to turn down.”

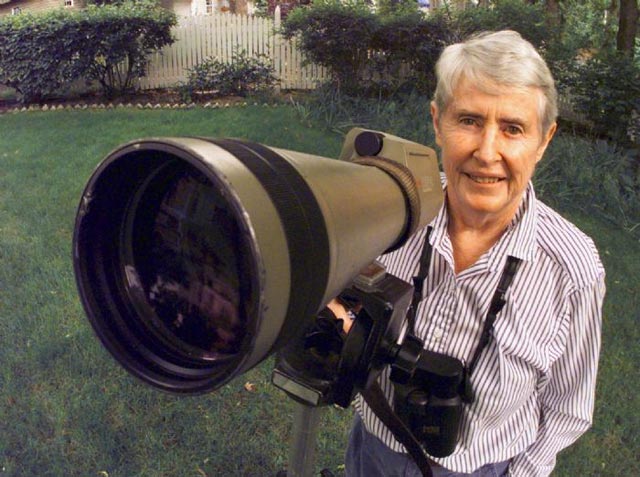

Phebe Snetsinger, Birding On Borrowed Time

“ So when did it finally happen, this awakening that has ultimately let me get the real world in focus and that has given me my bearing for navigating through the best years of my life? Probably when I saw my first Blackburnian Wabler in 1965.” When she reached 8000 species, she stopped listing

Elizabeth Seldon

with the American Birding Association. Birding had become a way of life for her by that point. Her journey had not been easy. Of course, cancer was the major battle she had to fight throughout her birding career, but she had to almost abandon her family to focus on birding. She had written in her memoir with a mother’s melancholy about having to miss her daughter’s wedding due to a birding travel commitment overseas.

Her global birding adventures had never been simple. Along with dealing with ominous pain and the side effects of her medications, she also had to contend with shipwrecks, landslides, and other natural disasters while birding in remote areas of the world. She was robbed, pursued, and even brutally attacked in Papua New Guinea, but nothing could stop her from seeing the birds she had always loved. After recording her 7,530th species, the Guinness Book of Records named her the “world’s leading bird spotter” in 1992.

Birding on Borrowed Time is more than just a bird watcher’s memoir. It is also a story about human determination, a person’s fight against a deadly disease, enduring female power, and, last but not least, the beauty of birding. By the time she died, she had become something of a celebrity and legend among birding and adventure travel enthusiasts. She inspires many birders who have followed in her footsteps, including me.